In what has become an annual tradition, we asked the Law School’s distinguished faculty to tell us about the last good book they read. The results cover a wide range of genres and topics, from law to history, nonfiction to fiction.

We’re giving away a selection of books from our faculty reading recommendations list for you to enjoy in the new year! University of Chicago Law School alumni who make a gift of any size by midnight on December 31, 2024, will be included in this drawing. If you have given at any time this fiscal year (including gifts made on or after July 1, 2024), no worries — you have already been entered in the drawing.

Make a Gift

Rules are as follows: Only University of Chicago Law School graduates are eligible. This promotion will run from July 1, 2024, to December 31, 2024. To be eligible, you must either make a gift to the Law School or send your name and address to:

University of Chicago Law School, Office of External Affairs

c/o Laurel Lindemann

1111 E. 60th Street

Chicago, IL 60637

While you may make multiple gifts, you will only receive one entry in the drawing. The prize winner will be chosen based on a random drawing of all who have made gifts or sent in their information. To receive the prize, winners must agree that their name will be available for publication as a prizewinner. Prizes are subject to change. Current employees of the University are not eligible.

This has been perhaps the most influential book on my thinking as a scholar (when I gave the speech at our Law School’s Midway Dinner a few years ago, this is what I focused on). After Daron and our University of Chicago colleague Jim won the Nobel Prize last month, I cracked it open again to see if I thought it would still hold up. There are some objections I have now that I didn’t have in the past, but other parts that I appreciate more than before. If you want to learn what two of the world’s most important economists think about one of the most important questions for lawyers (how to build stable governments and institutions), this is the book to read.

Ben is a gifted writer, who through a mix of the personal narratives of two men in prison and in-depth research about prison and correctional systems locally and throughout the world, shines a critical light on the injustices and need for opportunities for parole. A powerful and gripping book that taught me about how little we know about parole. A pleasure to read, but utterly painful at the same time.

This volume assembles the documents that are foundational to the University’s commitment to free expression. It includes reports from committees that were chaired by law professors—Harry Kalven Jr., Geoffrey Stone, David Strauss, and Randy Picker—as well as speeches by University leaders. The clarity and seriousness of thought in these materials has made the University of Chicago a beacon for free expression in higher education. At a moment when campus speech is contested nationwide, this volume is an important reminder that the University has been committed from its beginning to free expression as an essential element of its research and teaching mission.

The evolution of constitutional law of foreign affairs has been defined by practices of Congress and the executive branch, rather than through formal amendments or Supreme Court rulings. This book contrasts originalist and non-originalist theories to present historical gloss as a significant and enduring form of constitutional reasoning.

This beautiful, powerful novel winningly employs a multi-perspectival approach, spanning the years from 1850 to 2019, to tell the story of one of the greatest racehorses in American history, Lexington; the enslaved Black man, Jarret Lewis, who raised and trained him; and a wide array of other characters whose lives intersect across temporal, geographic, racial, and class lines. The novel wears its impressive historical research lightly, drawing the reader into the full vista of nineteenth-century America as well as a modern-day detective story involving both science and art history.

If you read one novel this year about the Louisiana Purchase, make it this one. Cable’s 1880 family saga, subtitled A Story of Creole Life, includes elements of Gothic romance, historical fiction, and mystery as it takes the reader into the complex social and political world of New Orleans in 1803. Cable wrote the novel in what turned out to be the twilight of Reconstruction, which makes its framing all the more poignant, as Black and white Louisianans alike wonder what the transition from French and Spanish to American rule will mean for their society.

I don’t read many books, so I didn’t expect to like If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, because it is a book about reading books. But then again, I teach civil procedure, which is law about how to use law; and I enjoyed playing The Stanley Parable, which is a video game about playing video games. Plus, If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler was given to me by Farooq Chaudhry, a former student of mine who knows a lot about books. So I gave it a go. It was then that I discovered that it wasn’t just a book about reading books. If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler is a book about You (yes, you: the person reading this book review) reading If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler. And the farther I got into the book, the more surprising, whimsical, involuted, and kaleidoscopic it became. By the end, it had become almost intolerable to read; but when I finished, I realized it was one of the best and most satisfying books I had ever laid eyes on.

This book is one of the classic books about cities, urbanization, and politics. David Halberstam called it “surely the greatest book every written about a city.” And for those interested in property, land use, local governments, and corruption, the book is a rich source of insight.

For the holiday issue of the New York Review of Books, I have reviewed three must-read books about the cruelties of the factory farming industry: Timothy Pachirat’s Every Twelve Seconds, Matthew Scully’s Fear Factories, and, especially of interest for our community, Alan K. Chen and Justin Marceau’s Truth and Transparency, a general study of undercover investigations, but focused above all on so-called “ag-gag” laws, laws forbidding reporting and photography of conditions in the meat industry. They argue vigorously that these laws are unconstitutional on free speech grounds. Before you launch into these books, and (I hope) read my essay, take a backward glance at Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, which said it all in 1906.

Trial by Numbers offers a highly accessible introduction to interpreting empirical evidence in legal contexts. Chilton and Rozema explain common empirical methods with clarity and relevance, focusing on intuition over equations. This tightly written and well-researched book uses examples pertinent to law school and legal practice, making it a practical resource for understanding empirical analysis in litigation, policy, and academic settings.

This is an entertaining, Pulitzer prize-winning, historical novel set in the 1920s with a post-modern vibe. It tells the story of a financier from multiple different points of view. Think of it as The Big Short meets Rashomon.

This novel about a wealthy financier in 1920s NYC is really three books—a novel about him (possibly a hit job), his (female) ghostwriter’s biography of him to “set the record straight,” and his wife’s journals about their life. You see three very different stories about what happened, seen through the eyes of oneself versus others, men versus women, ex post versus in the moment, and public versus private. You have to piece together what you think really happened, and which narrator you can believe about particular events.

Fehrenbach didn’t have a PhD and never had a faculty post, but his books should be the envy of every historian. His book on the Korean War is the best I’ve read. This history of the Comanche people is full of fascinating details and is brilliantly written. Even if you have no interest in Native American history, this book will entertain and inform you.

While reading 100 year-old novels for a Greenberg seminar this fall, I discovered So Big by Edna Ferber. Ferber wrote the novel while living in an apartment building that is a University of Chicago dormitory now. Chicago is very much one of the main characters, as the novel toggles between city and country (farmland that is now the definitely urban neighborhood of Roseland). It explores what it means to be great and content at the same time. And it includes a scene where the main protagonist is stopped because she doesn’t have a peddling license, which fired up this advocate for Chicago’s street vendors.

Our former Bigelow Fellow, now at the George Washington University Law School, has done a lot of great work on online harassment and other topics related to speech in our era. In this book she focuses on the need to construct opportunities for engaging, productive speech, moving beyond the absence of constraint that is the focus of our legal theory.

World War II espionage is an apparently bottomless well of inspiration for novelists of every era since the war. But no author captures the rich depth of internecine blood feuds, cross-cutting loyalties of Mitteleuropean tribes, and hard-won lessons of every belligerent's apparatchiks so well as Alan Furst. Night Soldiers is the first of more than a dozen novels in this series by Furst and remains the best, with the compelling tale of Bulgarian teenager, Khristo Stoianev, from his recruitment by the NKVD to the conclusion of the war.

This book uses the history of nutmeg, originally found on the Indonesian islands of Banda, as a way of elucidating the planetary crisis. He grounds the crisis in the mechanistic view of nature spread by Western colonialism.

Right now, I am reading Malcolm Gladwell’s Revenge of the Tipping Point, a follow-up to Gladwell’s surprisingly successful (at least to him) discussion of the science of how and why things go viral. Gladwell explains that, because so much has changed in the twenty-five years since his first book became a publishing sensation, he felt compelled to revisit his initial theories. Having appreciated Gladwell’s Talking to Strangers, I picked up this book hoping it would provide some insight into what’s going on in America today. What I did not expect, was that many of the examples that Gladwell uses to illustrate his updated theories are related to crime and criminal justice, just my cup of tea.

Orbital is denominated a novel, but reads more like a long-form poem. Set on an international space station, it spins out a single terrestrial day, comprising sixteen orbits, of the six-person crew. While things happens—a parent dies, a typhoon crescendos over the Philippines—the real thread of the book is Harvey’s startling weave of psychological detail with lustrous depictions of the earth traversed from above.

A political economist and a historian of the premodern world offer a brisk and pointed comparison of the trajectories of the Roman Empire and its present American successor. Close attention to the material and demographic bases of imperial power opens up surprisingly perspectives on familiar stories, and new puzzles for those thinking through the path of the world today.

I loved the fact that it is staged in Chicago, from the 90s to present date. It also captures so intelligently people’s cognitive quirks, that as I was reading the novel I found myself telling my Trademarks students about it in when we studied false advertising law. But what mostly stayed with me are the funny-and-sad and incredibly subtle and accurate ways it dissects human emptiness in our present time. It is one of these book that you want to not end, or to start reading over again.

This is a great, entertaining, and informative book about the development of science in the late eighteenth century. We learn about astronomy, chemistry, global expeditions, and even some ballooning. It is also about the role of leadership, the funding of science, and some of the interactions between science and the arts. It’s a book for everyone.

I discovered this book while browsing a bookstore in Dublin. It is the story of four adult sisters who have gone their separate ways in entirely different but successful careers. When one of the sisters disappears in the Irish countryside, the other sisters return to Ireland to try to find her, and the story is told in alternating chapters in each sister’s voice. Each sister is herself a fascinating character, and their interactions together are beautiful and real.

Immerwahr dives into the colonial history of the United States, and the parts often excluded when we think of the ‘logo map’ of the country—the shape that the map of mainland US would take if put on a logo. He explores the height of US empire at the end of the Second World War, in which the US controlled a large set of territories in the Caribbean and across the Pacific, and then dives into the contemporary ways in which the US continues to exert control across the world, including through the use of military bases. It is a fascinating read about parts of the US often overlooked, and a deep historical examination of US imperial ambitions.

A first-person novel told from the point of view of a solar-powered Artificial Friend. It is hard to say much more about the plot without spoiling it or failing to render it as beautifully as Ishiguro does. The book begins with Klara sitting in a shop window, and the reader discovers the world through Klara's eyes, as she manages to explore, understand, and misunderstand it, and develops her own deep relationships, quests, and failures. Written in 2021, but perhaps even more timely today.

I recommend The Jaipur Trilogy by Alka Joshi. The three books (The Henna Artist, The Secret Keeper of Jaipur, and The Perfumist of Paris) follow the lives of Lakshmi and her sister Radha, two poor Indian women who make their way from poverty to a comfortable life in Shimla, in the Himalayas, and Paris. The characters are richly developed and the narrative is compelling. Joshi pays careful attention to detail, to the political development of India and to world events as they affect the lives of the two women. I wish I could meet them!

I don’t read many memoirs, but I recommend this one, brilliant and sad, about neurology, cancer, and choosing a life path.

I read everything that Patrick Radden Keefe writes; he is one of those writers who has that ability to make you deeply feel embedded into the stories he narrates. This collection of stories—originally part of a series of articles that Keefe wrote for The New Yorker—dives into the lives of con artists, thieves, murderers, terrorists and more. It’s filled with empathy, humor, and tragedy, and offers a glimpse into the complex lives of the supposed worst of the worst.

Read everything Keegan’s ever written, starting with Small Things Like These. There is no better time to immerse with a character who must decide whether to comfortably allow things to drift along as they always have, or whether to surmount the fear of reprisal or ruin, champion the rights of the vulnerable, and take a stand against a dictatorial system.

Surreal yet brutally real, moving yet dryly funny, The Haunting of Hajji Hotak is a collection of short stories about a family of immigrants from Afghanistan. It ultimately comes together almost as if it were a novel, in which the reader bit by bit becomes privy to the dreams and nightmares of a family both strikingly ordinary and profoundly touched by war. It is called The Haunting of Hajji Hotak, but I was haunted, too. Whatever distance I had perceived between myself and the book’s characters had, by the end, been obliterated.

This book insightfully examines debates over the Constitution and the meaning of federalism during the interbellum period. It traces significant evolutions in constitutional thought during this era and presents a compelling argument for its relevance in contemporary constitutional interpretation.

This is hardly a new book—published in 1994—but the guidance (and humor) that it offers on a life of writing is timeless. Lamott makes clear how difficult writing is for even successful writers and even if you are born into it as Lamott was. It is an easy read that you could move through quickly, but Bird by Bird is probably best experienced bite by bite, so that you can savor every bit of it. Essential reading for those writing now—you will feel seen—and for anyone who is nervous about starting (Lamott makes clear that you should jump in and that the writing process mixes rich rewards with the struggle).

Technically, the final volume in a somewhat autofictional trilogy, The Topeka School in truth stands on its own as an unwaveringly close study of boys, men, and the ideals of masculinity to which they have aspired over the last half-century. This formulation is too dry, too didactic, however, to do justice to the rich and absorbing texture of midwestern family life Lerner brilliantly draws.

How is constitutional law like international law? Both of them struggle with the fact that there are no international law police or constitutional law police who can directly apprehend and sanction law breakers. That is because they are law for states, and so they must figure out how to establish legal rules without simply relying on any one state to enforce them. This academic but readable book argues that this is possible, but requires a range of strategies outside of simply laying down the law and expecting it to be obeyed. One of the most refreshing books about constitutional law I have read in a while.

I am reading a book called Separate, by Steve Luxenberg. It focuses on the history of racial experience and laws from the Civil War up to Plessy v. Ferguson, with particular attention on the major actors (Justice Henry Billings Brown, the author of Plessy; Justice John Marshall Harlan, famous dissenter; and Albion Tourgee, the lawyer who argued for Plessy).

The story of the close relationship between an old man (the long-time groundskeeper at an estate in Italy) and a young boy (the grandson of the owners). The old man has very few memories, and the young boy has an active imagination (and believes in monsters) and tries to help him remember so he can piece together the old man’s history. Some things he figures out, others he thinks he figures out—but we aren’t entirely sure on many counts.

Professor Kate Masur has written a magnificent chronicle of the movement for equality in the years leading up to the Civil War. A fascinating exploration of the debates over race, civil rights, and national citizenship that animated the antebellum period and which reverberate in today’s political discourse.

The best book I’ve read in years is Atonement, by Ian McEwan. The novel is a beautifully written, tragic love story, in which McEwan manages to evoke emotion and tribulation as effectively as anything I’ve seen on the page. It is also, in part, a war novel, in which McEwan captures the horrors of war for the soldiers who fight in it, the civilians who are caught up within it, and the doctors and nurses who must try to care for them afterward. But more importantly, Atonement is a meditation on writing, and on how readers interact with characters who, while fictional, trigger deep emotional attachments. McEwan suggests that to write is to play god with one’s characters. This implies that the reader should not treat characters as human, but instead see them as chess pieces moved by an invisible hand. Yet McEwan’s gorgeous, rich writing makes even that simple task impossible.

This million-copy bestseller is an Oprah’s Book Club selection and on Barack Obama’s list. Echoing Little Women slightly, it’s the story of four sisters, their parents, and one guy. It’s engaging, elegantly written, and has some emotional punch. The Chicago setting is a bonus. For fun, light reading, give this one a try.

In 1961 and 1962 Benjamin Britten was commissioned to compose War Requiem to mark the consecration of the Coventry Cathedral in Warwickshire, England. This fascinating book examines Britten’s musical representations of the body during war, situating his views on aggression, pacifism, and the beauty of the body through a combination of technical musicological analysis and philosophical analysis.

For the holiday issue of the New York Review of Books, I have reviewed three must-read books about the cruelties of the factory farming industry: Timothy Pachirat’s Every Twelve Seconds, Matthew Scully’s Fear Factories, and, especially of interest for our community, Alan K. Chen and Justin Marceau’s Truth and Transparency, a general study of undercover investigations, but focused above all on so-called “ag-gag” laws, laws forbidding reporting and photography of conditions in the meat industry. They argue vigorously that these laws are unconstitutional on free speech grounds. Before you launch into these books, and (I hope) read my essay, take a backward glance at Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, which said it all in 1906.

For 2020’s version of this list, I recommended Molly Ball’s biography Pelosi. I am still as strong an admirer of its subject as I was then, and hearing the story of her rise, battles, and triumphs in her own words (on audiobook, which she reads herself, with her own impassioned inflections) is even more enlightening and inspiring than Ball’s comparatively dry biography.

The Whalebone Theatre by Joanna Quinn is an absorbing novel, drawing you into the extraordinary mind of Cristabel Seagrave. It starts in her girlhood near the shore in England, where she is unsure of her place in her family but takes command of surroundings with her imagination and her play-acting. Eventually, she is pulled into the all-too-real drama of World War Two. It’s tremendous.

Quinn, a professor of ancient history at Oxford, shares the story, in lively prose, of the multiple economic, cultural, linguistic, legal, military, and political influences from Asia and Africa that contributed to the development of the “West,” in particular, Western Europe, starting around 2000 BCE. A fascinating history, rich in detail, and told in an appealing narrative form that makes it enjoyable for the non-expert.

Whether you are a fan of the Supreme Court’s opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008) or not, this biography of Samuel Colt will fascinate. Colt was a character, and this well-written tale of his life—from firing off canons on the campus of Amherst College at age sixteen to inventing the weapon that would change the balance of power in the Indian Wars—is endlessly interesting and delightful.

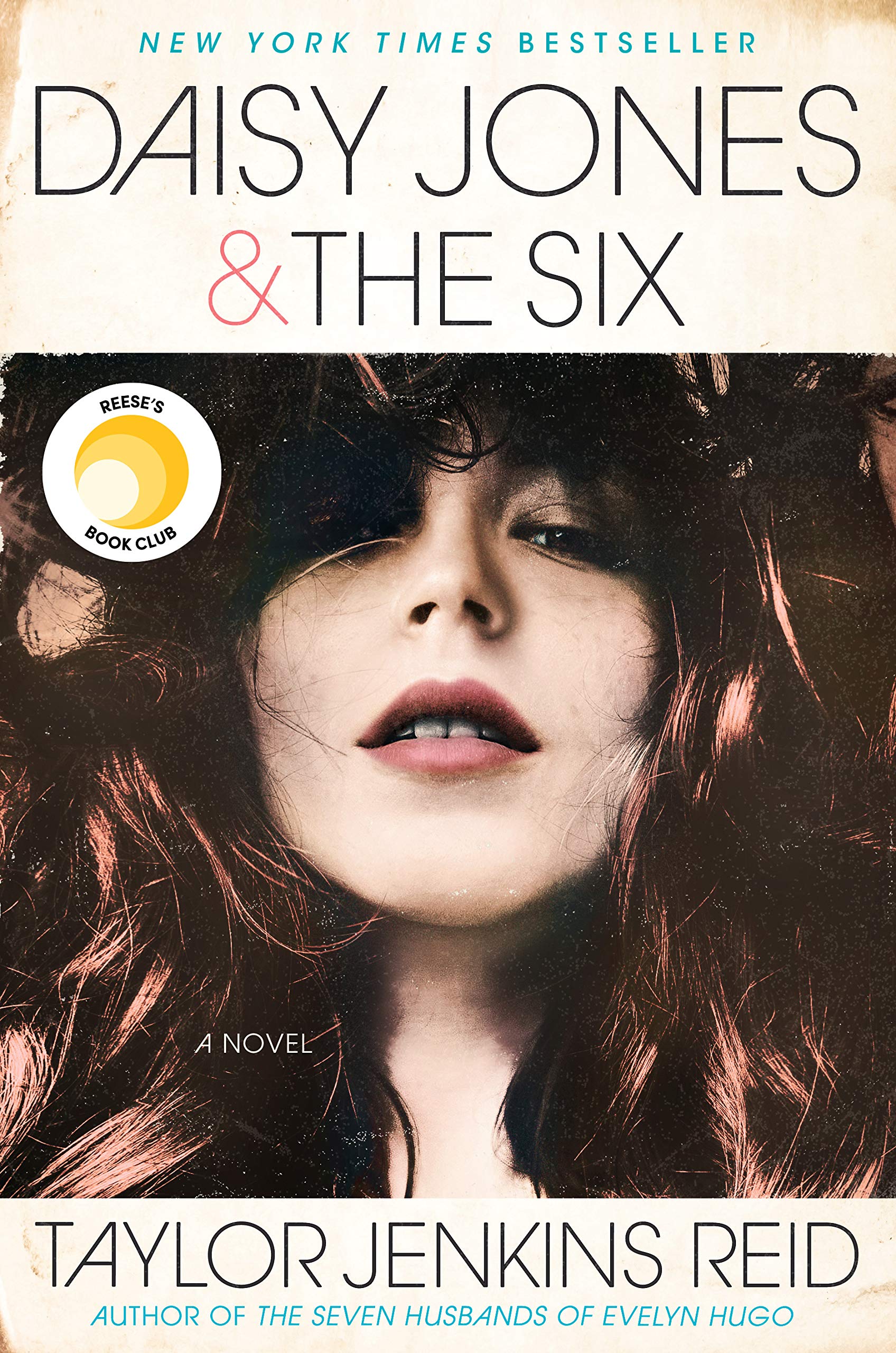

If you’re looking for a light and fun holiday read, Daisy Jones & The Six is for you! The book tells the story of a fictional rock band in the 1970s, loosely inspired by Fleetwood Mac. The author’s unique narrative style allows the reader to see how each character experienced the same events. There’s lots of drama and intrigue and it’s a true page turner. If you enjoy this one, I also highly recommend The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo, by the same author.

A page-turner of a novel about the intersection of criminal defense and Washington scandal. The main character is a career litigator whose childhood best friend, the former President of the United States, has been accused of murdering his mistress. Plot twists, personal entanglements, and several entertaining trial scenes ensue. The author (recently deceased) was himself an experienced DC litigator, from criminal trials to Supreme Court arguments, and founded his own law firm, Robbins, Russell, Englert, Orseck & Untereiner, where he was once my boss.

The American Presidency is the most important public office in the world, and it is perhaps also the most complex and challenging job. Through interviews with noted historians and even former Presidents, The Highest Calling presents profiles of individual Presidents and how they addressed the challenges of their time through this office. It is a fascinating examination of both this key institution and its occupants. It may prompt reevaluation of individual Presidents, and it will certainly elevate one’s admiration for the office.

The authorized biography of famed investor Warren Buffett is a bit too full of detail but if you have any interest in the history of investing and business, this is a must. I listened to it, at double speed. That is just about right. Buffett is one of the most important people of American business in the past century and this is the book to read about him.

For the holiday issue of the New York Review of Books, I have reviewed three must-read books about the cruelties of the factory farming industry: Timothy Pachirat’s Every Twelve Seconds, Matthew Scully’s Fear Factories, and, especially of interest for our community, Alan K. Chen and Justin Marceau’s Truth and Transparency, a general study of undercover investigations, but focused above all on so-called “ag-gag” laws, laws forbidding reporting and photography of conditions in the meat industry. They argue vigorously that these laws are unconstitutional on free speech grounds. Before you launch into these books, and (I hope) read my essay, take a backward glance at Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, which said it all in 1906.

Grover Cleveland is no longer a trivia question now that the president-elect is about to start his second, non-consecutive term, but he is still worth reading about. Our last libertarian(ish) president, Cleveland was a man of deep principle in an office for which that has not always been a prerequisite. I admire Cleveland, so much that I named my son after him, but even if you do not or don’t know whether you do, I think you will enjoy this book.

For the holiday issue of the New York Review of Books, I have reviewed three must-read books about the cruelties of the factory farming industry: Timothy Pachirat’s Every Twelve Seconds, Matthew Scully’s Fear Factories, and, especially of interest for our community, Alan K. Chen and Justin Marceau’s Truth and Transparency, a general study of undercover investigations, but focused above all on so-called “ag-gag” laws, laws forbidding reporting and photography of conditions in the meat industry. They argue vigorously that these laws are unconstitutional on free speech grounds. Before you launch into these books, and (I hope) read my essay, take a backward glance at Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, which said it all in 1906.

This noirish murder mystery takes place in an alternative version of 1920s America, in which St. Louis is nothing but a forlorn historical marker across the Mississippi River from the booming metropolis of Cahokia, an ancient Indigenous city that in Spufford’s imagining has become a multiracial, multiethnic tangle of skyscrapers, political intrigue, crooked cops (and honest cops), and, yes, jazz. The introductory maps and the excerpt from a traveler’s guide to Cahokia are remarkable works of imagination in their own right.

I greatly enjoyed Vision by David S. Tatel ’66. Judge Tatel’s memoir combines a fascinating personal history with reflections on the contemporary state of the law and the Supreme Court. Along the way, readers learn a great deal about the development of civil rights law in the twentieth century from one of its leading lights. Tatel speaks candidly about his experience of gradually losing his vision, writes poignantly about the great lengths he went to in order to hide his disability, and reflects on both changing societal attitudes about blindness and the remarkable ways in which new technologies have facilitated the better integration of blind people into the community. His discussions of cases he worked on, both as a litigator and as a judge, offer important context to better understand key landmarks in areas like voting rights, administrative law, the rights of accused terrorists, the separation of powers, the law governing disabilities, and environmental law. Of course, Judge Tatel’s fondness for the Law School shines through his memoir too, so readers will get a taste of what life was like for students here in the 1960s. David Tatel’s life and career continue to inspire our students and alumni, and Vision beautifully illustrates the obstacles he overcame and the vital support he received from friends and family along the way.

This book follows the consequences of a tragic school bus crash in the outskirts of Jerusalem in the West Bank, in which several Palestinian school children are injured and killed. It is a devastating, moving, and deeply empathetic account of the daily inequities and challenges Palestinians endure, which are compounded by a mass disaster. Thrall tells the story of the love of a father for his son through meticulous reporting and in-depth analysis of the impacts of the myriad laws and regulations that govern every aspect of Palestinian life.

This is an astonishing exploration of the danger of becoming what one pretends to be.

This history of American transcontinental railroads in the 1860s, in the right hands, is a model for many of our exuberant honeymoons with technology and finance. Stanford historian Richard White excavates the archives of Leland Stanford himself to reveal a tale of bloated railroads that rapidly overbuilt using the fuel of giddy money; rewarded pliant politicians with douceurs of property along new routes to extract thousands of miles of federal land grants; despoliated western territories and indigenous tribes; all while steaming toward widespread bankruptcy and government bailouts. The tale inspires curiosity about future marriages of technology and political favor that are destined to become unsightly but hard-to-discard scars upon our financial landscape.

In light of world events, I decided to reread this classic work about the Holocaust (Shoah). It is too easy to think the world has changed or people have changed in such a fundamental way that it can't happen again. Rereading this classic along with Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl, forces badly needed reflection on the essence of good and evil at this time of peril for the Jewish people worldwide.

I recommend American Anarchy: The Epic Struggle between Immigrant Radicals and the US Government at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century, by Michael Willrich, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and received the President’s Book Prize from the Society for American Historians. Willrich, a professor at Brandeis University, received his PhD in History from the University of Chicago. The book, a great read, explores our government’s war on anarchy in the early twentieth century during a time when the United States imposed draconian restrictions on free speech and re-wrote immigration laws to authorize the deportation of radical non-citizens, including such figures as Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. As Willrich demonstrates, it was during this moment that courageous lawyers for the first time advanced groundbreaking arguments for free speech and due process and inspired the emergence of our nation’s civil liberties movement.

So many people recommended this novel that I was prepared to be disappointed, but it is really a masterpiece. It tells a beautiful story of two children who meet under unusual circumstances and remain intertwined in one another’s personal and professional lives for decades. It captures better than any book I can remember how friendships can ebb, flow, and change over time, and how two people can misunderstand and underappreciate one another despite their best efforts to love each other. You definitely won’t want to read the last 100 pages or so in public—I sobbed steadily through the whole back end of the book.